The act of remembering

Remembering is not replaying the past, but reconstructing it. It matters what we remember. In each recalling we shape our very memories. In a birthday tribute, I recall the good things about my dad.

Today, October the 12th, would have been my Dad’s 79th birthday. I wonder what he would have been like as a 79-year-old? Not overly healthy in the first place, and having spent no time in his 50s and 60s working on building lean body mass or keeping fit, I suppose he might have been riddled with enough health problems to make him miserable. But who knows, maybe he would have seen the light and taken up walking and lawn bowls.

Lately, I’ve been struggling to remember the feel of my father. So seminal in my identity, this feels stranger to me than perhaps it should. After all, it's been 12 years since my father passed away, so it isn’t really a surprise that he is drifting out of my everyday consciousness. Becoming less solid and more ephemeral. And perhaps it means my identity is solidifying around my own adult experiences and choices, a good thing in itself.

It seems a perfectly reasonable thing then, in memory of him, to spend some time remembering him. The act of remembering is fascinating. You tug on one string, and others emerge. Why these memories, at this time, when there are 40 years’ worth to choose from?

I wonder, what of value do I remember?

A card, sent in the post, when I went away to University. A card with love scrawled across it. I don’t remember what the letter said, or what it looked like, but do remember that he took time to write to me. That he missed me. That it contained his hand writing, and his pet name for me – “my firsty born”. The only person to call me that. Lost now, that nickname, in his passing. That’s a sad thought that says something about what else dies with the people we love. I returned to that note time after time when I was lonely and homesick far away in Cape Town.

I remember the way he sat on the floor. Always the floor, leaning back against the sofa, watching TV or playing board games with us. Dishing out Christmas presents. Why, I now wonder, did my father spend so much time so low to the ground? Comfort, obviously. But perhaps there he felt in the heart of things.

And that he liked his butter and jam spread to the edges of his toast. BTTE. Butter to the edge.

I remember the shape and feel of his hands. Large, square fingers with large square nails. Dry, sometimes scary hands. Solid hands that could work wood into beautiful shapes. His flat, yellow wood work pencil tucked behind his ear. Tongue out while he contemplated measurements with his meter long metal ruler. I held his hand whilst he lay dying. After the diagnosis and the fraught mental battle towards acceptance, stiller and more at peace than he had ever been in life.

I remember the smell of wood being cut, rich and fecund – a smell that permeates my childhood and which always brings him immediately to mind. Coming out of the house into the dark of night, my six-year-old self in my pyjamas, looking for comfort, to find him working on some project or other. The sound of saw. The ground beneath it a carpet of yellow shavings.

And connected to that time, him teaching me to never box with your thumbs wrapped up inside your fists. A lesson in defending yourself from bully boys on the bus.

Memories are not accurate retellings of the past, recorded and played out on some internal YouTube. They are reconstructions. Recreations. Each one subtly new, and influenced by the moment of remembering. The memories we conjure up lay down stronger traces with each retelling. They rise to the surface. Become truth. It matters, then, what you choose the remember.

I often remember the criticisms my dad dished out. His flaws. My pervading sense of never being good enough to make him happy. Concentrating on those heightened moments, it is easy to forget the acts of kindness, of laughter, of joy. Of which there were way more.

Like…

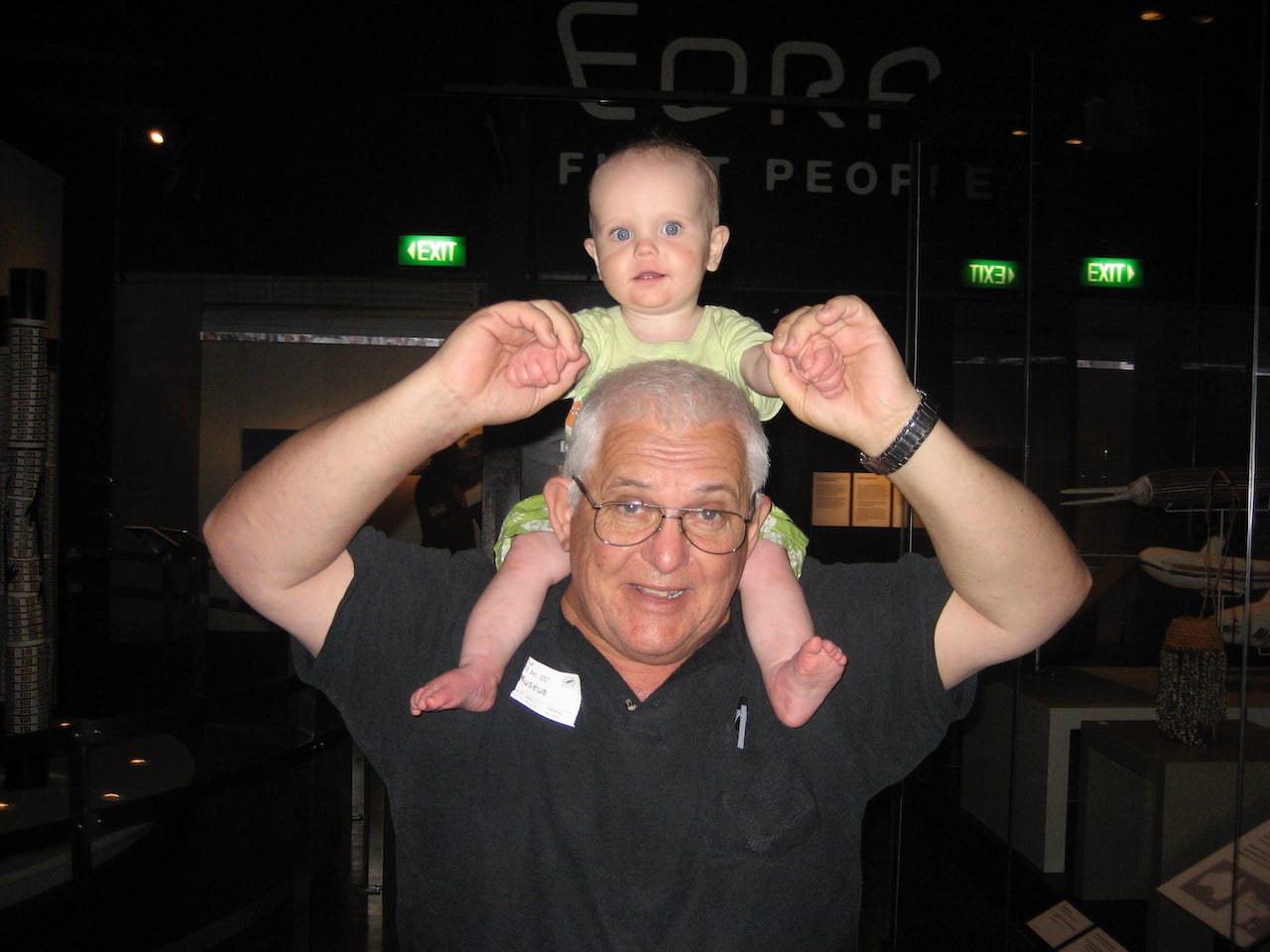

I remember when, expecting some sort of reprimand for my C in Afrikaans, my lowest mark ever at school and on this particular report card, he shrugged and said it was better than he could ever do. Or when, driving him and my baby son up the coast, I nearly killed us by pulling out in front of truck, he merely shrugged and said, “well, we didn’t die.”

I remember, being 15 years old and clocking his appalling grey colour as he leaned on the roof of his car, after his heart attack, my own heart pounding in my chest. I remember him taking a younger me for a spin on his motorbike. The vibration of the engine, the heaviness of the helmet and the feel of his leather jacket as I held on tightly to his waist. The Christmas tree made of string and wood one year (my favourite, although he thought of it with a sense of failure) from that house, and the smell of “soap snow” on the fresh tree we normally had. Often hunted down and cut by hand.

Occasionally beating him at Trivial Pursuit – our game. The sizzle of garlic and lemon butterflied prawns – his speciality. Him asking me how I liked my eggs, and laughing when I said I didn’t know because he hadn’t made them yet.

What will our children remember of us? How are we imprinting ourselves onto their memories? How long will they hold us in their hearts?

I remember how my Dad’s face lit up when he saw me, and how incredibly proud of me he was. Sometimes, maybe, that is all the memory you need.

Happy birthday Dad.

Love your Firsty Born.